- Crazy Pablo

- Posts

- Crazy Pablo: Gerhard Richter’s Family Secrets

Crazy Pablo: Gerhard Richter’s Family Secrets

Growing up, I thought politics belonged in history books or grown-up debates. I never imagined it could hide inside old family photos...

First time reading? Sign up here.

The Aunt – A Smile with Shadows (marked red)

At first glance, she looks gentle, maybe even happy. Richter's aunt Marianne holds the baby with a lightness that seems maternal and kind. But context changes everything. Marianne was diagnosed with schizophrenia and later murdered by the Nazi euthanasia program. Richter's brush, soft and blurred like an old photo, turns this personal memory into a collective nightmare. Her image floats in the space between remembrance and erasure.

The Baby – Innocence on the Edge (marked blue)

The infant in Marianne's arms is believed to be Richter himself. But he's not the focus, we strain to see his features, almost lost in the haze. The child represents both personal memory and the future unaware of its past. He’s being held by someone whose fate he cannot know. The tenderness of the pose contrasts brutally with the history behind it.

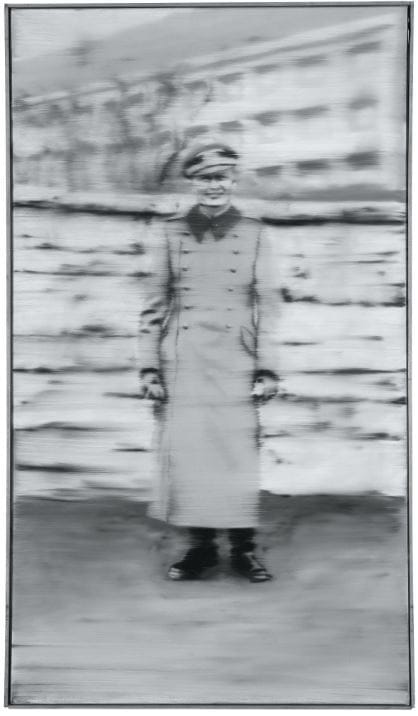

Original Photograph of Marianne Schönfelder & Baby Gerhard Richter, 1932 (Marianne aged 14, Gerhard aged 4 months) | Fun FactThis painting is part of Richter’s Photo Paintings, a series where he recreated blurred black-and-white family snapshots using oil paint. The blur isn’t a technical accident, it’s a philosophical gesture. By mimicking photography’s flaws, Richter questions how we construct memory and history. He once said, “I blur things to make everything equally important and equally unimportant.” Gerhard Richter didn’t only paint Aunt Marianne from a family photo, he also painted Uncle Rudi (1965), a portrait of his uncle in full Nazi uniform. By pairing these seemingly neutral family snapshots with historical weight, Richter forces us to confront how personal memory intertwines with collective trauma. The blurred effect isn't just visual, it reflects the ethical and emotional blur of post-war German identity. |

Think About It 🤔

How do personal photos become political? How do artists deal with inherited trauma? Richter doesn’t scream, he whispers. But the painting leaves a heavy echo. What parts of our own family stories are too sharp to look at clearly, and what do we blur out to survive?

How does it relate to the here and now? or What to say during casual conversation to show off your art knowledge?

The Personal is Political – “Richter doesn’t just show his family, he shows how private stories are woven into public history. His photorealistic technique makes us feel like we’re seeing a memory, but also a reckoning. In times of political denial or revisionism, these images remind us that no family is untouched by history.”

Now have another Look!

And If You’re Up for More…

You can find Aunt Marianne and other works by Gerhard Richter at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin - an essential stop for fans of 20th-century German art.

For a deeper dive, head to the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, where a major Richter retrospective is currently on view, covering his groundbreaking work from the 1960s to today. (Until 02.03.2026!)

Till next time, look again at your family photos, what do they hide? What do they reveal? Write back and tell me what you see.

Yours,

Inbal Z M

The painting itself is on display at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin,

when I visited the exhibition, I took a photo of it (with my mom)

In one of his most haunting series, Gerhard Richter painted four images based on historical photographs of a Nazi concentration camp. But instead of presenting the horror directly, he covered each canvas in layers of gray, smeared and blurred brushstrokes. The result is both present and absent, a memory you can’t quite grasp. Opposite the paintings hangs a large, foggy mirror. As you stand there, you see yourself (and my mom) reflected, dimly, uncertainly, alongside the ghostly remnants of the past. The viewer becomes part of the work. Part of the memory. And part of the ongoing struggle to face what can no longer be seen, but must not be forgotten.

Reply